The Making of Njardarheimr

Constructing Njardarheimr

When it came to constructing the Viking village, there were several different techniques that we knew were used by the Vikings. We have decided to represent several of the different types that they would have used to construct our village to more fully represent what was available at that time.

Bole House

One of the most prominent techniques you will see in the Viking village is Bole construction. In bole construction (bolverk), boles (half-logs) are slotted into corner-posts. When the wall reaches the desired height, rafters and tie-beams are fixed on top of them. The accurate assembly of the logs is vital. A well-constructed log/bole wall was waterproof and windproof, and provided good insulation. Gaps in a log wall could be caulked to prevent vermin such as mice and rats from entering.

This technique had the advantage of being very easy to maintain and repair. Sections towards the base of the building were more prone to decay, requiring heavy maintenance or even replacement. This version or construction made it possible to replace lower boards more easily, without the need to replace every single board of the walls, compared to some techniques. This is due to being able to break apart a lower board when it was no longer salvageable, then slide the boards above down in replacement of the removed section, finishing up with placing a completely new board at the top. The added benefit to this is that the older boards (therefore the more potentially compromised) are always at the base, the fresh timber more protected at the top. The weakness in this principle is of course the corner posts, which if beyond repair, would require a complete re-work of the structure.

Spell construction

Another prominent technique you will see throughout the village is Stave construction. This design uses a corner-post construction for the building (horn-stólpahús), where the construction rested on corner-posts embedded in the ground. Sill beams (aurstokkur) were fixed by mortise-and-tenon into the corner-posts, and planks were slotted vertically between them. The holes dug for the corner posts were filled with rocks. If the sill-beams did not stand free of the ground, they were protected from damp by placing stone or rocks below them (púkkát undir). A wall plate was slotted on top of the corner post and wall, fixing the structure together. The wall has the same appearance inside and out.

Notably, the biggest issue with this design is that every board is close to the ground and therefore every board is equally susceptible to decay, meaning all the boards would have to be replaced at the same time.

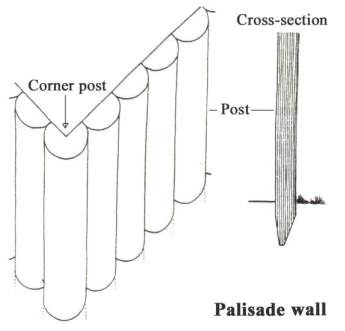

It should be noted that there were several different types of Stave style constructions, which can be categorized by age and method. We have primarily used the above style of stave construction, which was in use in the Viking age, however was a "newer" form at that time, starting to supplant the previous "Palisade Stave" construction. This design was the stólpaþil or palisade wall. In this case the wall comprised half-logs, tongued-and-grooved together (sporað), with the ends embedded in the ground, or thrust down into gravel. Wall-plates fitted over the top of the wall, and were notched (read) together at the corners. This construction method was known throughout Europe at the time when Iceland was settled.

Pit House

The final common style of construction you will find in our village is the Pit House construction. The pit-houses are reconstructions of finds of Icelandic and Norwegian pit-houses. Such houses were common in the Viking Age.

The pit-houses were placed half a meter below the ground, so that the floor lies below ground level. This helps keep them cool in summer and warm in winter., and could be used as food storage as well as living accommodations. The walls would have been made of wattle and daubed with a mixture of clay, mould, cow dung and water. We have used a pure turf style covering technique, as opposed to these original materials

Roofing

When it comes to roofing, we have again used two primary techniques that have been confirmed to have been in use during the Viking age.

Turf

The oldest of the two forms of roofing we have used is the turf or sod roof. This technique is made by first having a base layer of wood for the following layers to rest on, followed by around seven layers of birch bark, completed with one to two layers of turf. Birch bark has a high amount of natural bitumen oil in it, making it resistant to decay and allows water to run off with ease, giving the roof its waterproof properties. The soil and turf on the top have a double purpose, firstly to weigh down the bark (which would otherwise require nails to hold it down) and also as a fantastic insulation method. Such roofs were fairly low maintenance, lasting somewhere between 25 – 50 years with little to no evidence of leakage, depending on the humidity of the area in which the construction was raised.

Wooden Tile

The wooden square/rectangular roofing technique is the other style represented in our village today. This particular technique has very few benefits and most likely was used by wealthy people as a status symbol. It has little to no insulation property, making it much harder to keep a stable temperature inside, a detriment to construction that can suffer severe winters, such as Scandinavia. It can also be very difficult to maintain and to fully waterproof a building. During dry summers, the tiles can shrink (possibly cracking in the process) then requires time to soak in water to swell enough to be waterproof again when the wetter seasons of the year begin, leaving a time where leakage could be a problem. This could be mitigated by allowing the tiles to soak for a time in bitumen tar, making them water tight and stopping the issues with swelling and shrinking. If correctly prepared, such tile roofs can last centuries or even millennia, a good example being the Borgund Stave Church located only a couple of hours away, where the roof was not replaced until only a few years ago in the mid-2010s.

Colours

This village has used a variety of colors on our buildings, either the whole or part as highlighting colours. These have been verified to have been used in the Viking age and we have had help from the Danish Viking Museum to recreate these paints from the original pigments and techniques. You will see dark brown-black color made purely from bitumen tar, red-brown color used by mixing linseed oil with ox blood, mustard yellow from sulfur (very easy to obtain in Iceland) and a deep navy blue, which actually was from the use of undiluted Ox blood which, once oxidised, goes this deep navy blue that is found on the ceiling inside of the chieftain hall.

The two most notable colors that have been used, however, are the Spanish green on the chieftain hall and the Lapis blue used on the carvings of the same building. Both of these would have been rare and expensive in the Viking age.

Spanish green, as the name suggests, was created in Spain and only available there at the time. It was made using bronze metal flakes that would be oxidised in a solution which included arsenic, making it not only costly but incredibly dangerous to work with.

The Lapis blue was created by crushing up Lapis Lazuli stone and grinding it to mix into an oil base to create the vivid blue colour. As Lapis Lazuli was only known to be available from Afghanistan at that time, it required the Vikings to trade for it through the silk trade route connection they had established through Constantinople.

A Frame Ends

In our village, we have taken inspiration too from the Vikings artistic designs and flares, where we have decorated the ends of our houses with carvings of different animals and figures, all of which themselves play an important role either in sagas or mythologies from the Norse peoples. This may well have been done on the Vikings own homes (again, see stave churches as an example here). You will note that in our village, some of these A-frame ends have been left un-decorated, leaving them to resemble "lollipops". These few buildings are the only structures in the village where, due to the function that they play, were not able to be built using historically correct techniques, so have been left unadorned to differentiate the historic from the modern structures.

Living the Viking way

While there are a few hired to work here at Viking Valley, it is important for you to know that everyone of us are here firstly due to our own great interest in the Vikings and their culture, and secondly as a job. We are also not the only people you will find here; today we have a society of approximately 500 members to our village, meaning that, no matter when you visit, it is likely you will meet with people who are living in the houses that you will see, and you will be able to learn more about their specific areas of expertise about the Viking age. This might be academic knowledge on their beliefs, battle techniques and society structure; two textile techniques, blacksmithing or wood carving. Those living here live a life as close to the Vikings way of life as it is possible to do in the modern age, therefore you may find that some houses have either rope or chains across the doors. You are welcome to look through the door and windows but please respect the privacy of those living here, and do not enter a house with such a chain or rope unless invited to enter.

We hope that you have a wonderful day here at Njardarhiemr, Viking Valley!